What Is News?

Growing Culture

Within the span of the last 100 years there has been an imigration of people from countryside to cities. The result of this migration was the industrialization of the workforce. People have moved away from their land and into cities, no longer working on their farms but working in factories and now offices. This changed peoples’ needs and how their needs were met.

In the city, most of us are familiar with the things we must do to survive. On the land, people farmed for their food and utilized the natural materials around them for their other needs. Skills like iron-working and wood-working were common, there were also healers and story tellers amongst the variety of people who assisted each other within a local village or community.

For African-Americans, living off the land was different than it was for much of the rest of the world. This is because of two main factors. The first factor is slavery, which is well recognized and written about. A second, unmentioned factor, is the correlation between the westward expansion (1789-1849), when European settlers were given land for free, and the emancipation proclamation (1863), when slavery was outlawed in America. The chronology is deliberate, as told by the late Master Naba Lamoussa Morodenibig. “Before they freed the slaves they made sure that there was no place for them to go but back to the plantation they just left.”

Despite the harsh circumstances in which African-Americans persevered, they managed to maintain some of their cultural identity. Different aspects of traditional African cultures could be seen, heard and even tasted wherever African-Americans lived. One aspect of this cultural heritage are the plants people grow for food and medicine. Certain species of plants can be traced from backyard gardens in Chicago, to fields in Mississippi, through the port of New Orleans, along the hills and gullies of Jamaica, and across the ocean to the Nyala, Djoliba and Nile river cultures of Meritah (Africa). A seed is a powerful thing, especially when it brings an entire culture with it.

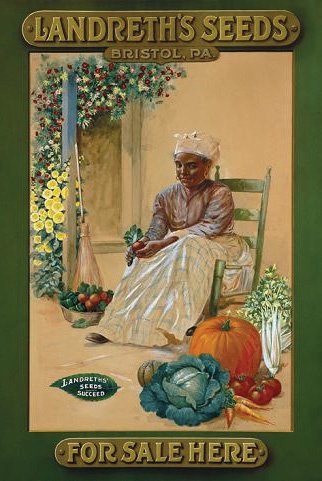

The Landreth Seed Company commissioned the above oil painting, inspired by a photograph taken by Rudolph Eikemeyer, for 1909

Another deliberate event took place not too long ago at Monticello, the home of the late Thomas Jefferson, 3rd U.S. President. An African-American culinary historian by the name of Micheal Twitty attended the event as did Barbara Melera, owner of D. Landreth Seed Co. Having attended the event separately, Mr. Twitty received a ride home to Washington D.C. from Ms. Melera. Their ensuing conversation led to the current African-American Heritage Seed Collection now offered by D. Landreth Seed Co. For those of you that have not taken responsibility for the seeds that your mother’s mothers and father’s fathers had preserved, this opportunity presents itself for you to regain some self-sufficiency and maybe reconnect to your cultural identity, whichever one that may be.

The collection is offered online and can be ordered from the company. Fortunately, some of the vegetable species are common and can be found locally. However, some are not and may have to be ordered. The collection comprises over 30 species. It has four varieties of pepper, cow peas, beans, cabbage, greens, pumpkins, tomatoes, gourds, watermelon, and a variety of herbs. The collection also includes millet, a staple grain of the cultures throughout the Sahel (Sahara) region of Western Meritah. Michael Twitty says that his love of plants and their history is partly rooted in the gardens his grandparents grew. “It’s kind of one solid line between myself and them,” he said.

Mr. Twitty recognizes something that many people fail to, that culture is something that we actively participate in. If we as individuals are not participating in any activities that our parents, their parents and our ancestors were involved in then we are not actively preserving our culture. We can’t just look the part. For any individual looking for a cultural link to the past, these plants provide evidence of African-American cultural ties to the traditional cultures of Western Meritah. Mr. Twitty’s research shows that throughout the era of chattel slavery, segregation, and up until these industrial times, African-Americans have held on to and cultivated these seeds of cultural identity. Will you forsake what your ancestors worked so hard to preserve?

C-Section

It is shocking to think that within the most "developed" nations in the world 1 in 4, 1 in 3, or 1 in 2 pregnant women end up having a C-section

Kemetic history, as taught in The Earth Center schools, comprises over 100,000 years of human history and tradition. We learn about our ancestral Neteru (Gods): Wisr, Heru and Aishat. We learn how Wisr and Aishat conceived Heru and how Heru was born premature. He was born weak, similar to the way that we, as humans, are weak. This knowledge is part of The Holy Drama, a historical account that gives us insight about our origins, human nature, our condition and what we should be aspiring to. Knowing our history provides us many benefits. Being aware that knowledge, wisdom and understanding are what we are here to gain through our human experience is just one of the things tradition teaches us. We look to our elders for guidance because of their life experience. We ask for their wisdom so we can compare what they know to what we are thinking. This provides us with another perspective when we are considering what decisions to make in our lives. History functions in this way too, but let us remember our vulnerabilities to those teaching us and be sure to ask: Do they have my best interest in mind?

1965, the first statistical year for Cesarean Sections, the U.S. national rate for C-sections was 4.5%. The C-section is a surgical procedure in which incisions are made through a mother’s abdomen and uterus to deliver one or more babies. A national rate of 4.5% means that if 1,000 women gave birth, 45 of them did so by means of C-section, the rest doing so by vaginal delivery called natural birth. A C-section is supposed to be performed when a vaginal delivery would put the baby’s life or mother’s life at risk of injury or death. However, in recent times the number of C-section births has risen dramatically. Statistics show a rate of 31.8% of births in the U.S. are C-sections, according to the Childbirth Connection, a maternity care advocacy non-profit organization. Statistics for China show a C-section rate of 46%, with other Asian and Latin American countries with rates over 25%. It is shocking to think that within the most “developed” nations in the world 1 in 4, 1 in 3, or 1 in 2 pregnant women end up having a C-section.

There are myths and realities associated with the increasing rate of C-section births. Two popular myths regarding this rise are: 1) more and more women are asking for C-sections that have no medical rationale, and 2) the number of women who genuinely need cesareans are increasing. Regarding the myth that more women are asking for a C-section, a survey by Childbirth Connection that asked 1600 mothers if they had initially planned to birth by C-section resulted with just one women answering that she had. The second myth, that more women genuinely need C-sections, refers to the idea that at this point in time there are more women that have complications; because they are older, have medical conditions, etc... However, statistics show that C-section rates have gone up in every category of expectant mothers, not just those at risk for complications. The reality is that there is a change in practice standards whereby a C-section procedure is pursued under all conditions, even normal ones.

A list of factors has been compiled by Childbirth Connection showing the interconnected reasons for the rising C-section rate. Among those listed: low priority of enhancing women’s own ability to give birth; the side effects of common labor interventions; refusal to offer the informed choice of vaginal birth; casual attitudes about surgery and cesarean sections in particular; limited awareness of harms that are more likely with cesarean section; providers’ fears of malpractice claims and lawsuits; incentives to practice in a manner that is efficient for providers. Further information regarding each of the aforementioned topics can be found on the Childbirth Connection website under the C-Section heading. We owe it to our mothers, wives and children to be vigilant about keeping childbirth a sacred experience that should not be interferred with through politics and economics. For information about what role politics and economics play in regard to childbirth watch ‘the business of being born’, a film with much good information about this topic.